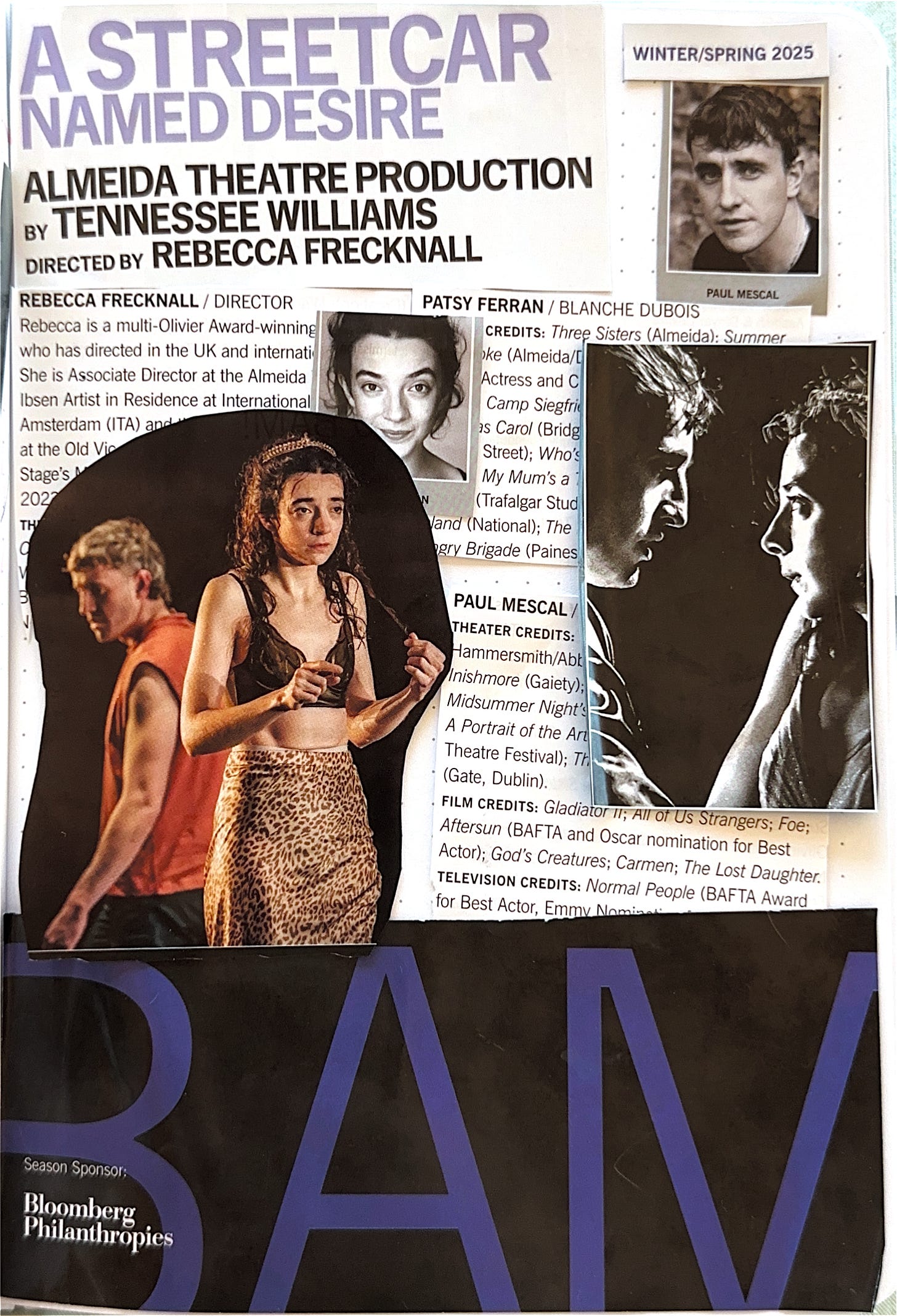

It only feels fair to preface this review with the fact that I spent close to 24 hours (nearly all of them staring at a screen, impatiently refreshing the browser) trying to obtain tickets for this show during the presale, which crashed the BAM website. I’d decided to ignore the Eras Tour despite being a lifelong Swiftie to avoid Ticketmaster pain and got hit over the head by the Eras Tour of the Winter/Spring New York theater season. Sure, some combination of the blood, sweat, tears, and admiration for Paul Mescal I came into this with have probably influenced my thoughts on the play. But it’s garnered plenty of acclaim in its own right as well.

Revivals are difficult, particularly when the original material is made into a movie, making the bar even further established. You can either hue as faithfully as possible, be meticulous in either a recreation of the first production or through following the letter of the play. Or you can choose a path so deeply divergent that it becomes an apples and oranges situation. I wouldn’t make the claim that Frecknall made the directorial choices she did purely in response to what’s come before—she’s spoken about prioritizing the sister relationship in the show, bringing her own particular interpretation to the material—but there is a definite earnestness in the presentation that wants to assert that this revival is new and, beyond that, twisting the prism these characters filter through.

In the most basic sketches, Streetcar is about Blanche’s return to New Orleans to live with her sister after losing both the family plantation and her teaching post in Mississippi. Despite Blanche’s cloying sense of superiority, she’s lost everything and is now at the mercy, she maintains temporarily, of her younger sister Stella and Stella’s new husband, Stanley Kowalski. Stella is intent on being everything to everyone, mediating between her husband and sister who instantly hate each other. As the play progresses, Blanche’s veneer as a prim and proper southern belle deteriorates and her chances at remaking her life in New Orleans grow slim. Meanwhile, Stanley puts it to his network to unravel the secrets Blanche is so obviously keeping in the hopes of making his wife abandon her sister. This singular focus on Blanche’s destruction is detrimental to his marriage (as well as his uncontrolled violent impulses), and this is the kind of play where nobody leaves happy or even unscathed. A proper tragedy.

While, in reading about the play afterwards, it seems that Blanche is positioned as the protagonist, I don’t entirely agree with this interpretation, at least based on the lens that Frecknall guides us through the play with. Classically, yes, she appears, drives the major change that begins the plot, and is most altered by the ending, but I’d argue that Blanche, Stanley, and Stella shoulder the role equally. They all (with the exception of Stella, who is the most clear victim in the play by the actions of both her sister and husband) share the role of protagonist and antagonist, trading moments of sympathy and horror as they jab at each other and the rest of the world. They both are responsible for plenty of bad; they also both exhibit humanity. It’s not so black and white, especially in this staging, as the SparkNotes funneling of Blanche as protagonist and Stanley as antagonist.

There’s a certain impression of modernization that’s inherent from the spareness of the stage design. The play is performed on an elevated square wooden platform. There’s a set of stairs leading to a balcony that in part exists to house the cacophonous drum set up and partially represents the upper floor of the apartment building. Around this platform that largely represents the “in bounds” action of the play is ample floor space hemmed in by brick walls. There are a few chairs, some pegs where jackets hang. There is no streetcar, no New Orleans flare, not even a divide between the rooms in the much discussed two room apartment that Stanley and Stella Kowalski reside in. It is a play that asks for a bit of imagination.

Bodies seem to be a fascination of Frecknall’s in her artistic choices. There are moments where the cast begins certain scenes with interludes of modern dance intending to set a mood more than be actual scene work in the play. She uses these bodies in the opening sequence and in the subsequent scenes as she establishes the claustrophobia and squalor of this city apartment building instead of relying on props. Characters not currently in scene prowl around beyond the edges of this platform. While Frecknall is inconsistent in her choice as to whether characters beyond the platform are diegetically involved in the story or not, leaving most of the actors on stage for the duration of the play does create a sense of small town claustrophobia, that everything you say or do is liable to be overheard and repeated. This is further accented by nearly all costume changes, beyond Stella’s, taking place on stage, stripping down to underwear in front of the audience and redressing. Just as the audience is always a witness, Blanche, Stella, and Stanley are always in one another’s space.

Music is also a large part of the scene setting, the thundering drums imitating the streetcars running past, the singer from the second story adding to that sense of city noise. While the musical elements felt a bit overstretched and the banging of the drums scared the shit out of everyone at every surprise bang, there was a certain sense of atmosphere they did succeed at conjuring.

The design is so immensely spare that the props that are used felt more impactful. Metal chairs are thrown around, accenting the violence. Blanche’s trunk serves as both a convenient seat and a first outlet for Stanley’s more fiery temper as he rips it apart, scattering her possessions across the stage, looking for papers. The poker party scene introduces an ice chest. There’s a red phone and a radio that becomes a central point of contention. Alcohol and cigarettes are actualized rather than left to the inflected imagination. The man in the row behind me complained of the smoke at intermission. These props tended to be proffered by the roaming extras around the stage whose main job seemed to be procuring and removing props, filling out parties, and compressing the private world that Blanche, Stella, and Stanley inhabit within their apartment.

For such a devastating play, there are surprising moments of humor. Stanley’s often mentioned membership to a bowling league feels joyfully absurd. There’s a bit about the Napoleonic Code, which Stanley fixates on the comedic effect. Blanche gets in a few laughs from the audience. The levity, which largely comes in the first act, plays an important counterbalance that invites the audience into investing in these characters, and the actor’s lean into this dimensionality.

Blanche is played by Patsy Ferran, who originally stepped into the role days before the first run when the previous actress had to drop out. Other reviewers have noted the unconventionality of Ferran’s casting. That while Blanche probably was somewhere in her thirties, the role typically goes to a more deeply middle aged actress who leans into a faded Southern Belle trope. Also, from what I’ve ascertained, Blanche’s mental unwellness, her potential schizophrenia, is usually played in a more heavy handed manner. While Blanche does unravel as the play goes on and her secrets are exposed, Ferran’s more stable hand on Blanche works for me. It makes it harder to see her coming undone as it happens. Her desperation and delusions feel almost plausible. The audience is able to hang onto the notion that she might just get herself out of this pickle she’s created, might pull the right strings, until it becomes abundantly clear that there was never any Prince Charming coming to save her. I think Ferran’s illusion of stability increases the gut punch of the ending when Blanche is forced to admit all her cards are on the table. She also introduces the idea that Blanche, rather than suffering from actual delusions, was simply trying to manifest her preferred world into existence, clinging to hope she knew was impossible because she had nothing else.

The play has its sweetest, softest moments in the short-lived romance between Blanche and Mitch (played by Dwane Walcott), Stanley’s poker buddy. Despite despising Stanley, Blanche develops a soft spot for one of Stanley’s friends she meets by chance, and for a time, he presents a silver lining in Blanche’s downward spiral. Walcott plays Mitch with a deeply effective contrast in temperament to Stanley. He’s soft, constantly worried about his ailing mother, and has a sense of gentleness that permeates his scenes. He seems to offer Blanche a romance like she’s never had before, though her past continues to haunt even this new possibility and complicates this otherwise very pure part of the story. Walcott proved to be an unexpected standout on the long tail of the play in my head.

I also think that her youthful look is actually an attribute instead of a distracting inconsistency, especially in Frecknall’s staging. Blanche is constantly babbling about how she was once beautiful, how she’s now too old and washed up to ever marry or have a happy life. She’s convinced life has passed her by. And her obsession with youth drives her into inappropriate relationships with young men and even teenage boys. This aspect of Blanche’s character is generally under explored in the play, more of a gotcha than a considered question as to Blanche’s ethics and morality, which seems to often be the case when the gender roles run this way. I think Ferran’s appearance is what makes this feel interesting and, to some degree, modern. There’s a pervasive obsession with youth in culture, and while many people are outwardly past the idea that you’re washed up at thirty, the internalized fear is still there, the frenzy to grasp at youth through whatever means and to whatever consequences feels incredibly modern. The dysmorphia of it is powerful; the incongruity plays to Blanche’s fraught mental state. Ferran plays Blanche as witty and polished and obnoxiously uppity as a facade over a ball of fear and anxiety to great effect, but she doesn’t make her a heroine easy to pull for either.

On the other hand, Stella, who gets the least stage time of the trio of leads, won my heart. She spends the play caught between a rock and a hard place, or, more precisely, her sister and her husband. Despite being an expectant mother, her needs always come in last. But, for being subsumed by the needs and desires and others, Stella is an integral character in the play as she’s one of the best mirrors for both Stanley and Blanche. While Stella is the most honest victim of the play, Anjana Vasan plays her with a fiery will that negates this box. Stella holds her own in the chaos the other two create with a weary tolerance for both. At one point, when Blanche tells Stella they should both run away, that she can leave her marriage, Stella informs her that she’s not in a position she has any interest in getting out of. She puts Blanche in her place for not being innocent in the list of Stella’s problems. Vasan delivers the lines with a sincerity and frankness that feels like it transcends an impression of Stockholm Syndrome, and she sells a Stella that’s as thoroughly bought into a relationship driven by sexual chemistry as Stanley is. Vasan’s performance, in a way, makes the play by holding Stella in a place of agency.

Paul Mescal is electric as Stanley from his ironic grins to the way he ambles around the stage. Stanley is a hothead. He throws a punch before he’s thoroughly thought the situation through. He scraps, he kicks a trunk barefoot, he stalks, and he giddily has Stella fly onto his back and gives her a piggy back off stage at the end of one scene. Stanley is so much his body. The physicality is remarkable. There was a magnetism that drew the audience forward in their seats. The sisters call him brutish and animal and a million other awful names of the sort, and that style of movement comes through, for sure.

But what makes Mescal particularly good in this role, which could go so easily flat, an unsympathetic abuser, a meathead, is the same element that made Mescal famous in the first place. He’s uniquely good at conveying complex, unspeakable emotions. He ties Stanley into the lineage of Connell and Callem and even Harry to an extent by understanding him as a man who truly cannot properly grasp and process his feelings, despite having plenty of them. In opposition to Mescal’s past rolls, Stanley externalizes instead of internalizes this struggle, but Mescal’s ability to recognize this gives Stanley an instant dose of humanity, positions him as a confused, messed up young man rather than a cartoon villain, which is an easily possible portrayal given his actions. He nails the rollercoaster of the tantrum that sends Stella running from the house to the bone chillingly deep remorse as he yells, “Stella,” in the iconic moment of the play. The sorrow feels genuine, the delayed understanding blooming at his physical alone-ness. Despite how startling and disconcerting Stanley feels through much of the play, I felt genuinely bad for Stanley as the sisters consistently hurled insults at him for being common, for being of Polish descent, for being animal. There’s no excusing Stanley’s violence, but this persistent picking does feel dehumanizing and wearing. There’s a distinct insight to Stanley’s point of view in those moments that makes the play much richer than leaving him as a stale, merciless antagonist.

This is partly aided by Frecknall’s interpretation of the climax of the play where the modern dance element is reintroduced as Stanley throws Blanche into a mob of people who strip her out of the debutante dress. This more effectively delivers on accenting the greater theme of society’s destruction of Blanche through their expectations, which many academic sources claim is the point of the sexual assault within the play, by involving everyone who has prowled around the edges of the stage, gossiped about her, torn at her sanity in this final moment of undoing, removing her from this gown that represents a more promising time. Yes, Stanley is the instigator, but the staging positions him physically separated from the true destruction, a more interesting position in my mind.

Blanche ends the scene curled in the fetal position under a thundering shower of rain, utterly devastated, certainly succeeding in showing the emotional impact of the moment. Also, in physically distancing her from Stanley, there is a bit of uncertainty, especially for those unfamiliar with the play. I saw others discussing the play saying they hadn’t understood what happened there or only knew what was meant by the scene, like I did, from prior knowledge and a bit of context from the dialogue prior as Stanley threatened her verbally and Blanche fended him off with a broken bottle.

While I can’t say if Frecknall intended any kind of ambiguity from the choice of staging or just found that the most tasteful or compelling way to stage the scene, I do think that it helped accomplish her apparent goal of creating a character study where all other elements are pulled back to examine complex people poorly handling the situations life threw at them and better access the larger themes of the play than even how it was originally written to be staged. By the end, everybody loses and there’s no one to pull for. They are, as we all are, fluctuating between protagonist and antagonist, depending on the reading. Regardless, I appreciate her not playing the scene for gratuitous shock value.

On a closing note, I think that the sparse staging is ultimately successful and an asset of this production. There’s something that makes it easy to remove yourself from something clearly set long ago. “That’s just how it was.” “That was so long ago, it has nothing to do with me.” There’s a kind of detachment that comes with the look and feel of 1947. Like how every time I read a classic, I don’t think it could possibly speak to my life and experience as a twenty-something girl in the 2020s. But they always do, and so does Streetcar. While the lines are all the same and sometimes throw in a funny bit of slang or a reference that doesn’t square with the modern world, the blankness of the stage allows the viewer to see how the story could play out today. How it could play out anywhere, the human bit not exclusive to New Orleans or even the American South. Blanche and Stella have faithful Southern accents that contrast with Stanley’s New York feeling accent—another subtle signaling holding him apart from the sisters—because there is a certain faithfulness to original, but they aren’t prescriptive. They don’t entirely define place or circumstance. I found this stripped version was calling out: these are just people. Maybe people you know. This isn’t the past. Or, at least, we’re not past this. There’s a reason to stage a revival, to watch one.

The entire production has a deep urgency that’s haunting. And, I think, it largely works.