There will be spoilers…

I finally got the chance to see Anora after its Oscar win brought it to my small town theater for a one week only special run. I caught the 4:30 $10 Tuesday showing in a nearly empty theater. My companions—two couples and a pair of friends all about my grandparents’ age—though small in number, made for fascinating and vocal viewing mates as they navigated a movie that was, most likely, not made with them in mind.

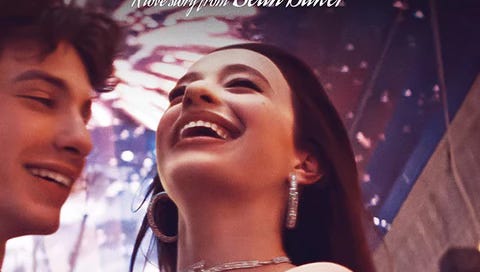

I wasn’t sure what to expect from the movie other than the promise that Mikey Madison is amazing. I’d seen the controversy over the lack of intimacy coordinator on set and Madison’s vocal defense of that choice (which felt, to me, like a product of trying to stay in favor with a director who, considering other controversies around the film, was into saving as much money as humanly possible). And I’d read the plot summary which posited a Cinderella story gone wrong for a Brooklyn stripper that spontaneously marries the son of a Russian oligarch and then becomes the target of the family as they try to undo their son’s mistake. Sounded interesting enough. Not being on TikTok, not much else about the various other controversies reached me prior, and I’m happy about that. I figured it couldn’t go full action movie if it’d bagged the Best Picture win, as well as pretty much every other major award they were nominated for.

To its credit, Anora is one of those movies that just looks incredible from the pop of the neon sign-stylized title card to the pan across of the private rooms at the strip club that set the scene. The color scheme, the lighting, the cinematography all feel incredibly dialed in from the opening shot, and Baker manages to capture both the seediness and the shine that pops off the screen and forces you to pay attention as the story is established through quick cuts of Ani finding clients on the floor of the club to take to the private room. These quick cuts efficiently establish what her day-to-day life looks like before the twist that incites the plot while also grounding the film’s visual palette. I was pretty hooked the moment I noticed the tinsel strung into Mikey Madison’s hair. Anora simply looks better, in a single shot, than either other Best Picture nominee I saw (A Complete Unknown, Wicked) ever achieve.

Once Ani is introduced to Ivan and his friends, since she’s the only dancer who knows how to speak Russian, the film takes off running. She dances for him, then he hires her for multiple private meeting at his house, a towering, gated mansion. Ani immediately clocks how puppy-like Ivan is a child trapped in a twenty-one-year-old man’s body. He’s inexperienced, for one, but he also hasn’t ever had to make a bed or clean up for himself in his life, and the many scenes of him playing video games that he’s heavily invested in as Ani lays on his chest further drives the point home. While Ani is tough and well versed in the realities of her work, she does start to find Vanya endearing, and though she ensures she’s being well compensated to spend time with him, there is something that appears genuine between the two.

When he hires her exclusively to blow it out on his last week in America before returning to Russia, Ani gets to experience the life she glimpsed within the mansion on steroids. Baker throws everything he can at the Vegas montage complete with a private jet, a massive high roller suite, running through the casino (and being unperturbed at losing a lot of money), and splashing around in the pool. This is Ani’s Cinderella at the ball moment, surrounded by more opulence than she can almost believe.

It’s at this point that I want to come back to something interesting about our protagonist, which is that we know almost nothing about who she is beyond what immediately unfolds in the film. Over the entire narrative, we gather that her grandmother spoke exclusively Russian, which was how she learned the language, that she shares a cramped townhouse with her sister in front of a noisy subway line (only revealed through scenes of Ani packing up her stuff), and her mother lives in Miami with a guy that’s not her father. Beyond that, Ani’s past and the specifics of her situation are kept opaque. There’s assumptions to be made based on her profession, as well as small costuming details like Ani’s purse being a dupe of the very trendy Prada crystal bag. But we never spend any time intimately inside of Ani’s head. We can’t understand where she came from or her motivations beyond what’s scraped off the surface. Yet, she’s still a compelling character, somehow, largely owing to Madison’s deeply nuanced portrayal as she follows Ani’s rollercoaster of going “on” and “off.” This element has largely been used as proof that both Baker is the wrong person to be telling this story and attributed as a lack of depth, but I think, in this particular case, it works to have our protagonist at an arms length. She’s a withholding person in general; she doesn’t trust easily. Why would she trust the viewer implicitly either? (Whether this is Baker’s story to tell and whether that matters is a whole other debate, and I think I’d rather keep this to purely what’s on screen. Maybe it was intentional, maybe it was a lucky break covering major holes. Who knows. It’s interesting.)

The end of the Vegas trip is also the next major turning point in the plot and an important moment for characterization that is then challenged later in the movie. When Ivan mentions the idea of marrying Ani for the green card so he won’t have to return to Russia, at first, she tells him to stop teasing. But he goes on, talking about wanting to escape his stifling family and their expectations, stay in America, make a life with Ani. He says he’s willing to give up the blank check his life has been written on to make it work with her. And she starts to believe him.

Remarkably, you can watch in Ani’s eyes, the moment she buys into this idea that she—forced to be wise beyond her years—and Ivan—the man child—aren’t that different after all. They both have a dream of escaping their very different circumstances. She takes this earnestly and marries him, it seems, not just for the money but because she likes this idea that they’re jumping out of the plane together. They marry at a Vegas wedding chapel, and the fantasy seems, almost, like it’ll work. As a narrative, this moment hinges on the audience buying into the purity of Ani’s belief and their true moment of elation afterwards that made me smile as giddily as they were. This movie kills it with the montages.

Of course, the high has to come down, and while Ivan vehemently fights against his godfather’s two henchmen sent to wrangle him when word gets out about this marriage, he eventually flees the house while still pulling up his pants, without his new bride in tow. And so begins the action movie-influenced part of the film. Ani is left with the two men and a Home Alone-style scene unfolds where the hapless goons struggle to fight back against a girl who’s clearly spent most of her life fending for herself. The violence is often played for physical comedy, and they’re all broken by the time Toro, a priest enlisted to be Ivan’s American keeper, arrives. Though Toro seems manipulative in his speech to Ani that she’s as much a victim of Ivan as they all are, that Ivan is never kind or thoughtful, sincere or considerate, Ani seems to hold out genuine hope that she does have a real marriage. In these moments, she feels more motivated by a yearning for stability than access to a tightly held pocketbook. Her naivety shows as she tries to cling to this, but Madison’s portrayal pulls from a deep place that is intellectually opaque but emotionally clear to the viewer. So she goes with them on the quest through New York to find Ivan before his parents arrive.

It’s through this misadventure-filled journey that the truth of what Toro is saying begins to become apparent. Ivan doesn’t answer Ani’s calls and makes no attempt to contact her. And, in the time they spend together, her captors soften. Igor, who tied her up with a phone line at the house out of fear, which she’ll never forgive him for, tries to make small gestures to ask for her forgiveness. He feels as innocently caught in this web as Ani. Ivan betrayed them all in different ways, and the longer he stays gone, the more apparent that becomes.

This is undeniable by the time they ultimately locate him in a private room at Ani’s former club with her biggest rival. Ivan is off his face and indifferent to the situation as he is reclaimed, despite Ani begging him to remember Vegas and the promises they made. The first cracks deepen as Ivan’s reaction to being found implies that this pattern isn’t new. It’s all part of a game. Still, even when offered $10,000 to sign the divorce papers and walk away, she wants to hold onto the marriage.

When Ivan’s parents arrive on their private plane, it becomes clear that Ani’s lost whatever edge she held through her hostage situation. She could physically scrap with the first round of bad guys, but as she tries to make a stand for herself with these immensely rich and powerful people, she quickly realizes her hand is played out. Her bravado can’t save her. And, on the steps of the private plane, Ani is forced to reckon with the truth of Toro’s words as Ivan, now somewhat returned to his body, declares that they are getting a divorce and, as much as he may resent his parents, he’s going back with them. Ani’s illusions of this rich boy ready to sacrifice it all for her crumble. He is not like her after all. By the end of the exchange, she wants the divorce as much as the rest of them.

Ani, with Igor to accompany her, is sent back to New York in coach, given one night to pack her things from the house, and returned to her apartment in Igor’s beat up car. The comedown is harsh, played up by Baker’s stylistic choices to create this contrast. Toro and his crew prove to be honest as Igor gets her the money from the bank before dropping her off, and the whole charade is over. When Ani quits her job at the strip club, she tells her friend she hopes they honeymoon at Disneyworld, and her friend correctly guesses that she’d want to stay in the Cinderella suite in a rueful bit of foreshadowing. Because this is a grown up movie, set somewhere, it seems, in the late 2010s, Ani’s Cinderella story ends at the point of despair—when midnight has come and the horse and carriage are now a ton of rats. Like how Cinderella retains the slipper, though, Igor returns the Tiffany’s engagement ring they’d taken from her as a final show of goodwill. It’s unclear if Ani will get her job back. If this entire episode will be a strange blip from the year she was twenty-three or if it will echo further. The film doesn’t expand upon this.

Instead, in the final scene, Ani pushes Igor’s driver’s seat all the way back and straddles him, seemingly out of the blue. While they’ve had bubbling chemistry, it almost feels like this is the only way Ani knows how to express her gratitude for his kindness. But this quickly sours, and she turns to hitting him before collapsing on his chest in tears. While the scene itself felt somewhat drawn out, strange, and confusing to watch, it also feels like a fitting end to the movie. It offers a small insight into some of the larger repercussions of Ani’s life prior to the events of the movie and this whirlwind few days, and notably, while she’s screamed plenty, this is the first time we see Ani cry. It’s the first slip of the mask of her steely resolve and nearly cathartic as she’s been through plenty that warrants a good cry. One for ambiguity, her sobs and the windshield wipers soundtrack the credits, and the resolution never comes. While the ending presents interesting questions, it does drag as far as pacing is concerned as Baker draws his non-ending out too far.

The ending for Ani and Ivan is both deeply predictable and satisfyingly surprising. The logical part of your brain always knows that the spoiled brat will align with the money when pressed. We all know he won’t be able to overcome who he fundamentally is as a person—and his taste for comfort—for a whimsical dream carried on passion. He behaves like a child in every other way, so of course, his moments with Ani are only worth a half-assed teenage rebellion. It’s doomed from the start, but Baker along with Madison and Mark Eydelshteyn, who plays Ivan, sell every moment with such an earnest sincerity that the heartbreak of Ani’s realization hits. In a way, it positions the two characters through an interesting prism where Ani does have the advantage over Ivan of the complete freedom of having nothing to lose. It’s not much, but it adds an interesting flavor to the dynamic.

In closing thoughts, I want to highlight a thread to this film that I didn’t expect, perhaps best illustrated by an anecdote from my theater viewing experience. A man in the back, after an audible laugh from his few other audience members, grumbled, “It’s not a comedy.” To which a woman a few rows down replied, “Yeah, but that was funny.” I tend to agree with her. There’s a lot of brilliantly executed dry, sarcastic, and ironic humor that brings much needed levity to the film. It made me laugh or smile at an absurd joke a number of times through their wild goose chase to find Ivan. It is a genuinely funny movie, and to the guy in the back, that is an attribute that a serious drama can coexist with. Also, I will say that a lot of the movie is in Russian, so, unless you happen to speak the language, it’s probably best enjoyed when you’re in the mood to read subtitles. I can’t say that from the chatter I heard leaving the theater that any of my companions enjoyed the film either as much as I did or at all. They mostly found it perplexing, strange, and hard to follow. Which, to a degree, is fair. It’s not a perfect film by any means, and I think I felt more fondly for it in its delivery as a pleasant surprise since I don’t take Oscar wins to mean all that much in terms of my personal hype scale.

This is one of those films that I’m glad I went into blind. I’d only seen maybe two videos on social media about it and heard it recommended by another actor. I went and read up on the various opinions on both the film itself and Sean Baker afterwards. And there is certainly a glut of opinions. I had a friend list all the reasons the movie was bad for things that had nothing to do with the actual film when I said I’d gone to see it (it’s on her list to get to eventually still). And while there was plenty of valid criticism in there and issues I was totally unaware of that probably would’ve influenced how I viewed the movie, I don’t think I get this experience often enough of going into something on a lark, knowing nothing about it, and having feelings and a response purely honed by how what happened on screen reacted in my particular brain. I think those bigger cultural conversations are important, but it is also complicated in a way that makes it impossible to consume art for what it is. Growing up online, steeped in these conversations, it is usually the facts around the art and, somewhat, the hive mind opinion that is settled on, that precedes everything I consume. Sometimes, it’s a treat to just be surprised by a story and know nothing of its creators.