please don't read my journals

thoughts on the new Didion book

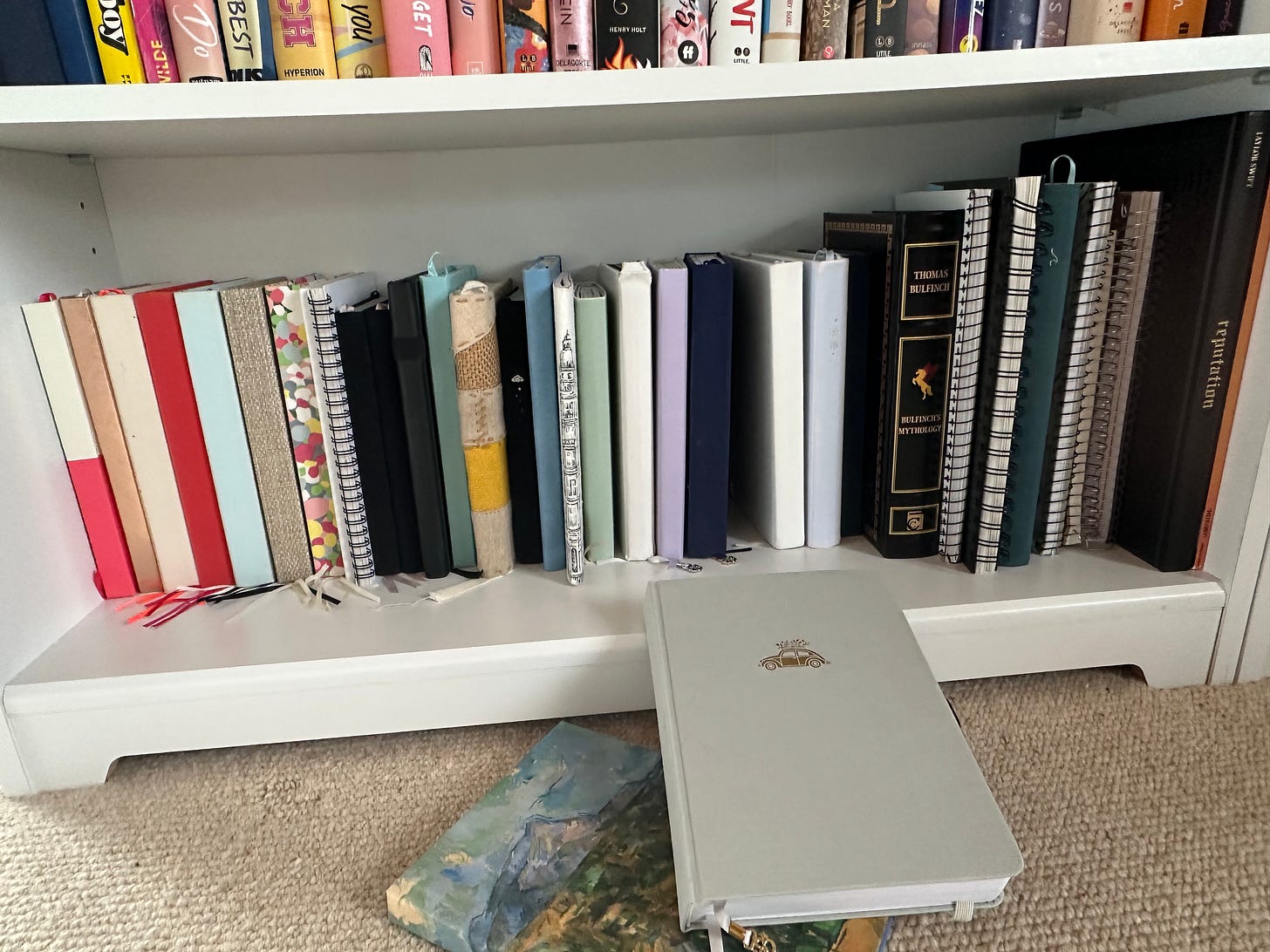

“Can I read your journals?” my brother said randomly in the middle of winter break. He’d said it into total silence, nothing in the conversation inviting a question like that. I wanted to turn around and bolt up the stairs. Install myself in front my bottom bookshelf where the journals I’ve diligently kept since 2017 are lined up. I’ve written a journal entry nearly every day since I turned 13 and started eighth grade. There are a lot of them now, the daily journals joined by the yearly bullet journals I’ve constructed since 2021 that hybrid a bullet journal, a scrapbook full of Instax photos, and a junk journal. I’ve never read my journal entries back. At the moment, I don’t think I ever will, but I might change my mind one day. For now, they sit on the shelf as a record of my existence. It’s a habit.

Obviously, my answer was no. Automatically. It wasn’t that I was really worried about what he would find or that he might get personally offended. Sure, I’ve complained about him as much as any other human I’ve spent an extended part of my life around. I’ve written down things I wouldn’t share publicly. But mostly they’re boring accounts of everything that happened in the day, one page mostly listing events or nonevents, work completed or procrastinated on. Occasionally, there are three page entries that loop around a particular anxiety trying to untangle the knot. They’re occasionally dramatic or juicy, but would only hold interest to people who know me well. I assured him with some authority that he would be incredibly bored. The conversation moved on, but I still wonder about leaving them all there unattended. They’re my brain on paper and while generally harmless, the long tail echo of your past self is never high up on the list for public consumption.

I’ve been thinking a lot about the implications of keeping journals and what happens to them when you die, especially if you’re a person of note. There’s a lot of juicy ethical dilemmas there. These were questions I never considered when I started my first journal at thirteen, assumed to be far from my potential demise. But, in the last few months, the conversation keeps circulating back to me. It first arose in October in Dublin when my friend and I stumbled into the National Library of Ireland by accident and wound up in the Yeats exhibit housed there. In the center of the exhibit are glass cases containing his journals. There are a few notebooks open to specific pages, fairly indecipherable at a distance and written in a style that even someone proficient at reading modern cursive would struggle to parse. I felt generally fine about this exhibit, mostly because I couldn’t read the pages very well. But it did immediately stick me with the image of my journals propped open and left on a particular entry to be consumed by the public if they wanted to peer down through a glass cube.

I was then confronted by the question again while reading Didion and Babitz at the start of the year. I have plenty of passionate (negative) feelings about the book, which you can read in my review, but the premise of the book is that it’s written using a collection of journal entries, unsent letters, received letters, and other random items unearthed from Babitz’s apartment after her death and deposited at the Huntington Library. Now, I don’t have a problem with this on its face, writing a biography from papers left to a library collection. This is what happens with the work and personal papers of many famous writers in many well regarded libraries. What got me in this situation is that Lili Anolik knew Eve Babitz personally for years and had interviewed her extensively for the first book she wrote about Babitz. And never once did Eve suggest Anolik open the closet door and make use of her personal papers. Nor, did it seem, did Eve leave any wishes to make these items publicly accessible. While I could be interpreting this situation entirely wrong, this connection to Eve made it feel like Anolik was accessing this new information, full of details Eve never chose to divulge, behind her back now that she was dead and unable to stop it.

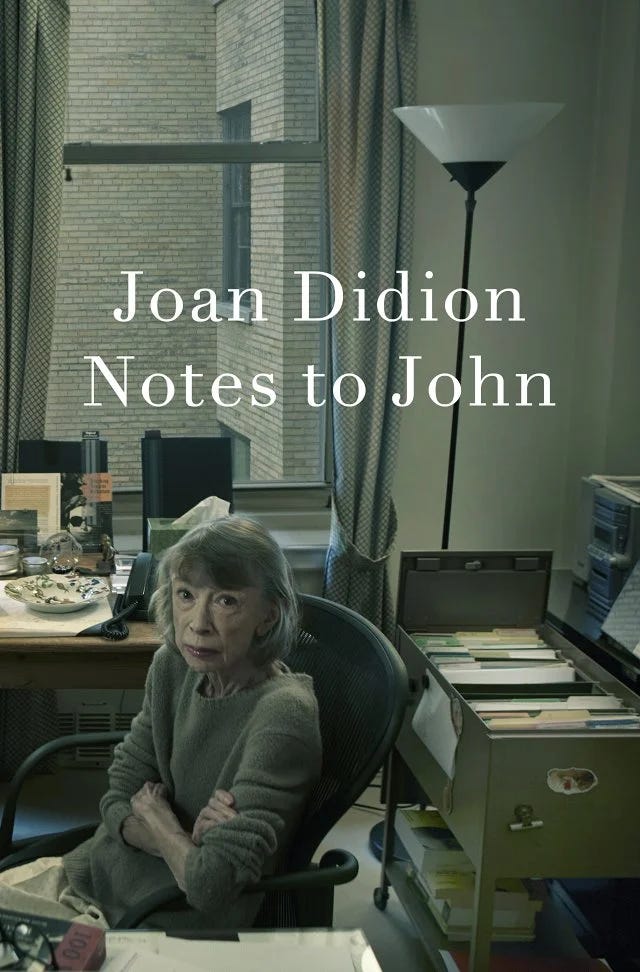

Finally, there’s the recent announcement that the world will be getting another Joan Didion, conveniently in the wake of her latest renaissance as a literary it girl. Or, perhaps, she’s just symbolism for today’s internet literary it girls? Either way, people are reading lots of Joan Didion, not that they ever stopped. Considering that Joan passed away at the end of 2021, how are we getting a new book? Well, Notes to John, is being constructed out of a journal that Joan kept in 1999. Not just a journal documenting mostly inane details about her days like mine. No, a journal where she made notes on her sessions with her psychiatrist. A journal that she seemingly wrote to her husband John. The notes on the sessions, according to the blurb, cover “alcoholism, adoption, depression, anxiety, guilt, and the heartbreaking complexities of her relationship with her daughter, Quintana.” Also included, reflections on her childhood and, the only thing possibly justifiable for public consumption, reflections on her work. Considering that in Anolik’s characterization of Joan in her book is that she was too withholding, too sterile in her recounting of messy details, and too self protective in her writing, even about difficult subjects, I cannot imagine Joan would want this journal out in the world.

Keeping a journal is, at its core, an intimate, private act. It’s an exercise in putting words into the world by silent means, compressing thoughts into pages for an audience of one. The only response you’ll receive is from your own brain. There are so many other means of expression, ways to excise thoughts from your body, that journaling shows an intentionality to work things out within the confines of yourself. The pages invite you to share half-formed thoughts, vent, spiral, cry, and figure out what you want to say on these topics when you’re ready to share the thoughts in the open. On the subject of Joan, she shared her thoughts about Quintana’s death, John’s death and their lives, with the world already. She crafted bodies of work with intention. Publishing this journal, to me, feels disrespectful to the large body of work she completed for a public audience.

While I understand the desire to consume every last drop of what your favorite writer produced, there’s something disquieting about reading a work not intended for the public. Like the controversy around Go Set a Watchmen’s publication that seemed to clash with Harper Lee’s wishes. With the writer no longer around to object or have any kind of feeling about it, these estates must feel free to capitalize on the presumably large amount of money they stand to make while feeding fans’ curiosity. No one loses, right? But these posthumously released pieces do impact a legacy. They become part of the cannon and judged alongside intentional works. Journals, as used in conflation with diaries, are generally agreed to be written with an intention of privacy, making even boring ones exciting to read for the pervading sense that it’s wrong. That you’re seeing something you’re not meant to.

So, then, what is the answer with these journals? Writers write. From what I can tell, we tend to be a large portion of the journal keeping population, and we probably, as a generalized population, have tons of notebooks ranging from personal musings to project notebooks. We have planners and grocery lists and all kinds of esoteric detritus from people who still use paper. And if we become famous writers, someone might have an interest in all these paper bits we’ve hoarded. What does one do with that?

I can’t answer for all of us, except to say that if you’re a creative person of any kind with any sort of feeling about what happens to your unreleased work when you die, please stipulate your wishes in your will. There will be some like Sinéad O’Connor who will happily let their estate exploit the materials. Some will be like Lee, who once stated that she had said all she wanted to say and had no interest in publishing further work. And then, perhaps, there will be a middle ground that is most common.

All of this makes me wonder, what are my wishes for the journals that line the bottom of my bookcase? For one, no one touch them for a very long time. Thankfully, no one will care about them for a long time, if ever. But, hypothetically speaking, if I became a figure that would make anyone care to look at all the journals I left behind, at present moment, which no one should hold me to, here’s where I draw my personal ethical lines. Don’t publish my journals in full, like they’re doing to Joan. No one wants to, or should, read that. Please don’t dig through my personal journals after my death, if I knew you in life. I could see donating them to a library collection, letting anyone dedicated enough to travel to the physical place and take them out of the box take a more intimate look at who I was as a person through the years. I’d just hope they wouldn’t be exploited in someone else’s book either. The project journals, the world can have them. Work and process and drafts and a look at how the gears turn? That’s the valuable insight, much more than who I was mad at on August 15, 2022 or what I ate for breakfast on February 7, 2025. I guess I won’t really care, cause I’ll be dead. And if nobody wants them? Throw them in the garbage. I’m far too sentimental to preemptively burn them. I also don’t have that much to hide.

I think, the heart of this newsletter is just about the gut feeling when encountering something private from someone who no longer around to defend their wishes. This is probably a more pressing feeling for those of us who do journal. In doing a bit of light reading about the publication of Sylvia Plath’s journals, one of the journal publications that stands out in my mind as being among the best known, I found a Reddit discussion in r/books soliciting reader reactions. “i caught that you said “invasively” and i’ve had this sense while reading that she wouldn’t have wanted these journals published. my own journals contain the very depths of my mind that i’d never share with anybody, and that’s just what i assume with hers,” one user wrote in response to another comment. “Invasive” was a word that appeared over and over through the thread, though there are many others in similar threads who feel entitled to all of an artist’s output after their death by virtue of them being a public figure. Maybe that invasive quality is easily missed if you don’t have a deep relationship with a journal yourself, if you don’t know your own deep intensions behind the process.

Hopefully, this and other reactions around the internet can provide context to the non-journalers out there. While journals are often fascinating texts even in their mundanity, I want to know the journals that I do read are because the author wanted them available for public consumption. I guess that’s my ethical line.