bite sized theater thoughts

featuring Three Sisters and The Boy (Oedipus retelling)

This fall, I’ve been lucky enough to immerse myself in an art form that I’ve only recently had the pleasure of getting into—theater. 2025 might just be the year I personally discovered by love of theater between starting the year watching a recording of Andrew Scott’s Vanya then making a trip to New York to see A Streetcar Named Desire and now living in a city with such easily accessible theater that I’ve been attending shows somewhat regularly. It’s so interesting to see how stories morph and change through various mediums, and there’s truly no better way to entirely disconnect from the world than through good theater.

These little reviews come with no authority. I don’t really know enough about theater to properly review it, but I wanted to note down my takeaways from these productions and document my thoughts. I remind myself I didn’t know much about discussing books or music when I started either, and the only way to build that skill is to record your thoughts and then reflect on them further. And I’ve gotten to see some real gems that I want to remember, being treated to work of some of Ireland’s greatest playwrights including Ciara Elizabeth Smyth and Marina Carr.

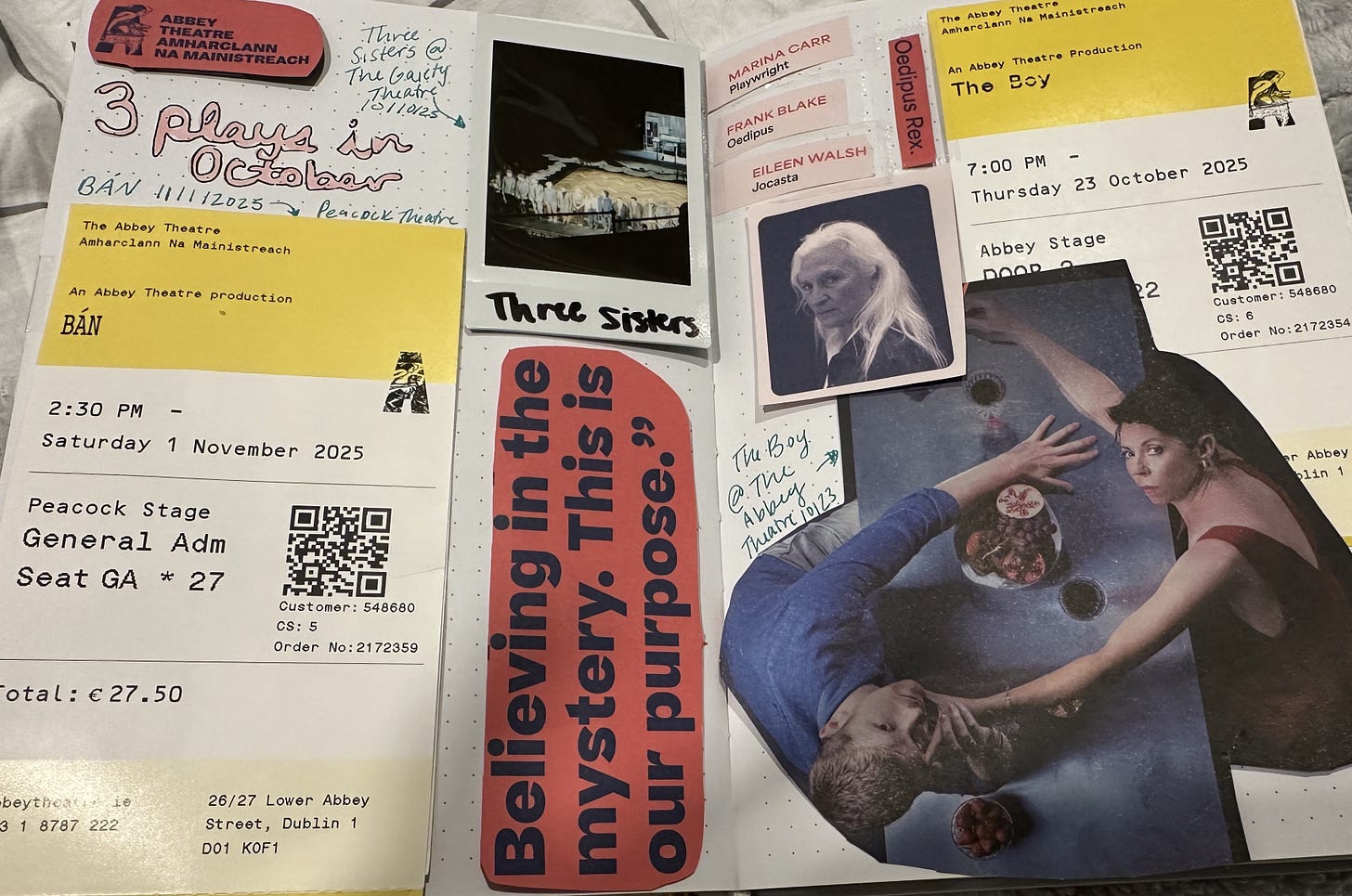

Three Sisters

Playwright: by Anton Chekhov, adapted by Ciara Elizabeth Smyth

Director: Marc Atkinson Borrull

Design: Molly O’Cathain

Theater: Gaiety Theatre, part of the Dublin Theatre Festival

Moscow is the white whale of the Chekhov classic, Three Sisters. As the play opens, we meet a very excited, caffeinated Olga talking to Irina on her birthday, pontificating on how all their problems will be solved when they move to Moscow. At the opening of the play, it’s obvious why the sisters are looking for an escape. Their father has died, and with his passing came the disappearance of the rich world of soldiers and military men filling their parties with interesting guests. They’re left sad and lonely. Olga works at the school, getting more responsibility and having more of her time taken from her in a role she doesn’t really care about. Irina, the youngest, begins the play eager to do something that few in her immediate circle partake in—work—to find a sense of purpose, but as the play goes on, she takes on a series of jobs that all feel draining and meaningless. Masha, the middle sister, is dark and moody and takes her unhappiness with her high school sweethearts marriage to a school teacher out on an affair with a commanding officer who comes around their parties. Beyond the sisters’ own unhappiness is their brother, Andrei, who is a fallen genius, built up to be extraordinary and then failing to do anything with the talent and ability people made so much of.

This is a play with a cluttered cast of characters. They all easily reveal themselves to the audience, making them rich and interesting, but there are a plethora of threads to follow, necessitating the lengthy nearly three and a half hour run time. My writer brain could definitely see a few extraneous moments that could’ve been cut, but there was also a joy in luxuriating in scenes that only existed to deepen the character relationships. I’m not familiar with the original Chekhov play, so I couldn’t quite spot what exactly in the text had been changed or modernized. I was surprised when after the intermission the focus changed from the interpersonal dramas unfolding in the manor house—as the sisters tried to make their lives less miserable while clashing with Andrei’s wife Natasha over the running of the house—to the aftermath of a fire that engulfed the whole town. This raising of the stakes felt like a sudden switch in tenor. While the second half was much more unwieldy, it was fascinating to see the often referenced Chekhov’s gun principle in action as a minor character flashes his gun seemingly inconsequentially in an early scene which comes back around at the climax of the play. The moments are so far apart that I nearly forgot my sense of anticipation when I first saw the pistol.

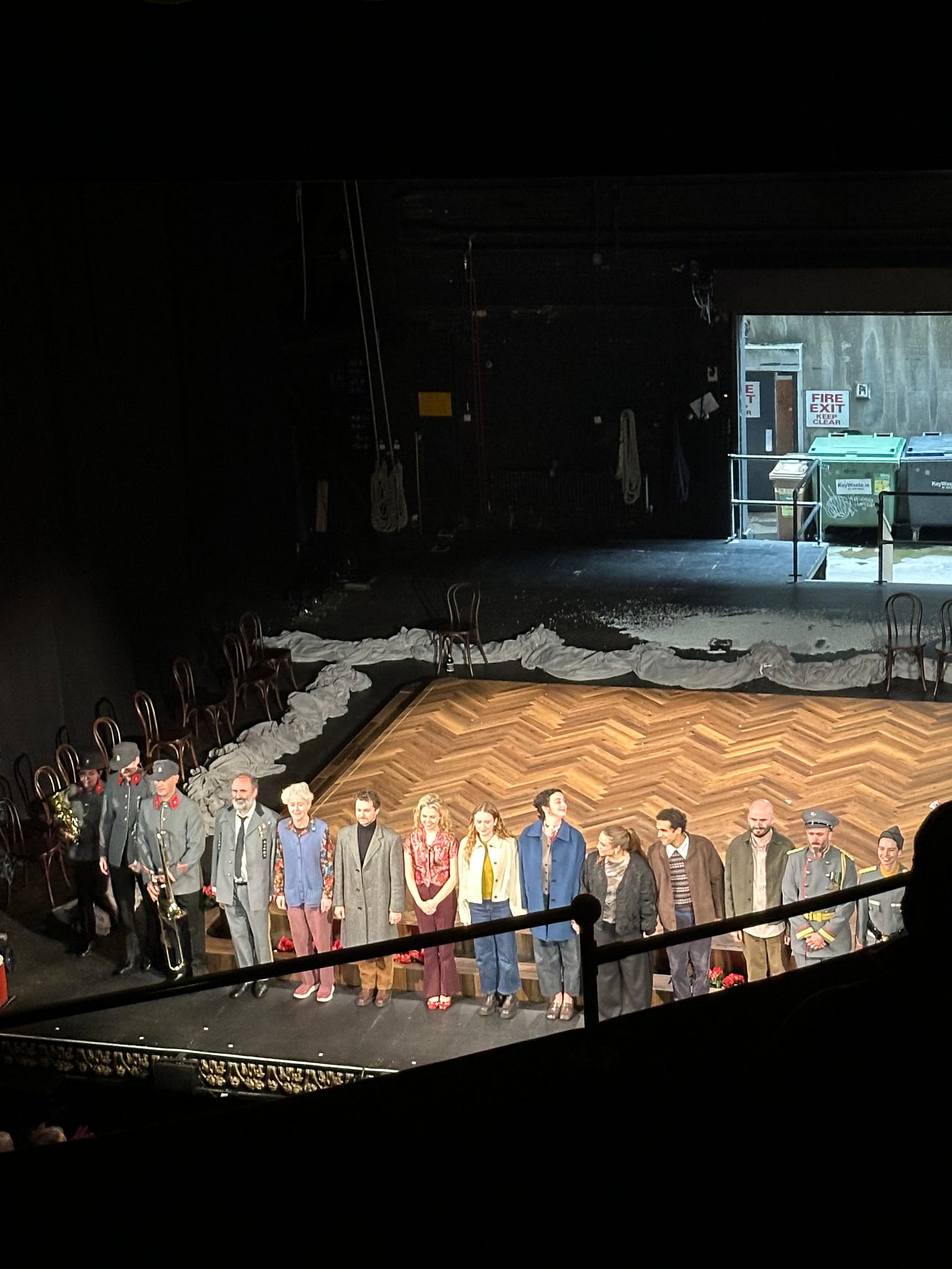

Given that my touchstones for theater are relatively limited, I was surprised to see that the staging felt deeply reminiscent of the production of A Streetcar Named Desire from this spring at BAM. There was a raised, square platform in the middle of the stage, and for much of the show, a long table and chairs were the only set pieces. Similar to Streetcar, the main action takes place on the raised platform with characters sometimes walking like they’re on a tightrope around the edge or stepping on and off it. Much like Streetcar, it was quite blurry on whether those that were off the platform but standing or sitting on the periphery were a part of the scene or simply transformed into a sort of prop themselves to emphasize the claustrophobia of all of them living in the same house. Towards the end, the grey curtains around the perimeter of the stage fell, exposing the backstage area of pulleys and emergency exits, perhaps symbolizing that the story has left the house and was out in the wider world. In a relatively sparse staging, they did make use of a few interesting effects including a fire table insert into the main dining table to symbolize the fire that takes hold right before the curtain falls for intermission and the use of the back load-in door through which all of the characters exit in the final scene into the actual alleyway behind the theater.

Overall, I found it to be a deeply entertaining play focused on nostalgia, memory, and how one copes with a distinct feeling of stuck-ness. There’s also an interesting emphasis on the value of having an imaginary place to run away to in your head. While maybe not among my favorite plays, it was beautifully acted, especially by the actresses who played each of the three sisters, Megan Cusak, Breffni Holahan, and Máiréad Tyers.

The Boy

Playwright: Marina Carr

Director: Caitríona McLaughlin

Designer: Cordelia Chisolm

Theater: The Abbey Theatre, part of the Dublin Theatre Festival

For a creative writing class in undergrad, I’d been forced to read Oedipus Rex, and I can’t say I really enjoyed it. I attended this play mostly because the tickets were cheap, I knew Marina Carr was a lauded playwright, and Frank Blake, one of the lead actors, was in Normal People. When I took my seat in the theater, I didn’t know how wild of a ride I was in for. The play opens with a frame scene of The Shee taunting Oedipus that all is not as good as it seems from his palace with the wife he adores, hinting, even, that he’s about to go blind. That quick scene creates the pin in the circle we return to by the end of the play after traveling back decades to watch the full horrors of Oedipus’s fate unfold.

The source material here, and really all Greek tragedies, are quite strange in the sense that we don’t have characters to pull for in the way that modern audiences so deeply want a clear “good guy.” All of these characters have done horrible things. They also all have at least shreds of sympathy. But they’re less stories where you want the protagonist to triumph and more a meandering cacophony of tragedy that you watch unfold with a sense of horror and intrigue. People’s lives fall apart, that’s really all there is to it. Perhaps it would be worse if there were truly redeeming characters. It would be too heartbreaking.

The play then jolts us back through time to when Oedipus’s mother, Jocasta, marries Laius, the king, who has kidnapped a boy, Chrysippus, which has brought the wrath of the gods and the original curse. We all know about Oedipus, the son of Laius who is destined to kill his father and marry his mother. We watch as Laius tries to outsmart the curse, sending the baby away to the mountain to die (this was the first moment of the play that made me physically recoil as I watched a tree full of babies in various states of decay descend from the ceiling. the play has no fear of gore or images that will surely come back in nightmares) and again see this behavior repeated when Oedipus, who hears of his curse from The Shee, runs off into the wilderness to escape from his (unknown to him) adoptive family in a bid to escape his curse. Both men think, for a span of decades each, that they’ve managed to outsmart the silly gods. Both hold a deep conviction that there is no longer a use for the gods, that man is god now.

The play then functions to prove how misguided and stupid they are, the weight of this only added to by the fact that everyone in the audience at least has a vague notion of what’s about to unfold. This point is further driven home by scenes that are interspersed where The Shee, who serves as the intermediary between the gods and the mortals and is painted like the town kook in Oedipus’s reign, goes to speak to the gods, who take the form of a gold encrusted Godwoman, the Sphinx, who gets to have a tail, and Moon. These scenes add the main injection of humor to the piece as the gods chit chat with one another about the happenings on earth, ribbing each other and throwing jabs in every direction. They create an interesting chorus and show how petty and silly even the godly beings are. They grapple with their going out of fashion among the mortals, even as they hold the ultimate power to curse and send plagues, to alter their lives. As noted in the opening remarks in the program in a quote from the director, this is a particularly interesting thing to explore as my generation and those directly adjacent have less of a relationship to God than previous generations, much like what is being reflected in the play. “Here, the myth is explored through the presence and absence of gods. What is Man’s law versus God’s law—and which one is right, and right for whom?” McLaughlin asks.

This is the bit of the play that stuck with me most deeply. The play doesn’t exactly argue that being godless is what does these characters in, but it does beg the question about what moral deterioration happens when one views themselves as the ultimate authority. Rather than analog to our modern times making the argument that there has been a great loss in the recession of Christianity, it instead offers a cautionary tale about the people we choose to make modern, mortal gods and the dangers of anyone putting themselves in that position—think tech billionaires, influencers, etc. The only thing that can come from that much hubris is Greek tragedy. Instead, the play made me think about the importance of staying rooted to something beyond yourself and beyond traditional signifiers of wealth and power, having some kind of spiritual connection whether that be to God or gods, nature, literature, karma, or something else.

Back to what was actually presented on stage, I was deeply impressed with the acting, especially from Frank Blake, who played Oedipus, and Eileen Walsh, who played Jocasta. I didn’t think that I could be compelled by the love story that blooms between Oedipus and the woman we know to be his mother, though he does not. But there is a genuine chemistry that’s undeniable and shocking. It’s excruciatingly painful to watch because it feels like the only genuine love exhibited throughout the play, and after Jocasta’s horrible first marriage, that’s what we want for her. This exacerbates the tragedy of what’s unfolding, and Carr is wise to play this up. To this end, after Oedipus and Jocasta deliver a victory speech to their thriving empire that has major Hunger Games vibes and is interrupted by The Shee, here to deliver the news that blows up their lives, Oedipus goes on a long, private monologue wrestling with the news. This feels much more nuanced and much more aware of the trauma that they have both endured than the source material, which, to my memory went something like: Oedipus is horrified by what’s happened and gouges his eyes out. Instead of just capitulating to the grief of having fallen for the curse, we watch him agonize with Jocasta about the news, debate whether they can keep it a secret and continue on as they were, finally happy, while deep down knowing that he cannot go on with that knowing in the forefront of his mind. While obviously horrifying, it is also a deeply moving, beautiful scene that made my stomach churn and my heart genuinely go out to them.

As far as the staging, most of the play takes place in the confines of this vaguely Grecian looking platform. There’s a table that’s moved in and out and occasionally other set pieces that drop from the ceiling, like the horrifying baby tree. A ceiling insert ends up playing a large role in creating many of the godly effects. It certainly felt expensive and highly detailed and at once struck both minimalist and maximalist chords. There are bright flashes of light that are disorienting as an audience member and no fear of prop blood getting all over everything. The play is meant to be uncomfortable, thematically and visually, and they succeed at that in spades.

In all, I found this to be a fantastic retelling of Oedipus’s story and far more compelling than reading the play on paper—as most plays actually brought to life usually are. It showed me the value of the Greek tragedy still, a form that I’d previously found to be stiff, somewhat formulaic (likely because it’s taught in creative writing classes literally as a formula), and pointless because we already know everybody dies at the end. Carr does a fantastic job showing that the point can be so many other things beyond an ending and that knowing the destination doesn’t negate the journey and can sometimes be a boon, if you’re a skilled enough writer to carry the audience along without the tension of wondering how it ends. Truly, with enough skill like The Boy shows, an ending you know at the start can still feel surprising anew when it finally arrives.

Sadly, I didn’t get to see the second play in the duo because it closed before I had time, but I’m sure it was a fantastic continuation, delving into Antigone and continuing the story of generational tragedy and collapse. This was truly an unrivaled treat.